SESSION 1 | Interacting with the Bible

Life would be lonely and confusing if we did not know about God.

Without a sense of why we are here, understanding the meaning of our lives, or knowing our origin and destiny, we are left to wander into each moment as if that is all there is.

The Bible gives us a framework for understanding our world and our place in it.

We learn about a Creator who fashions us in His image, invites us into His forever family, and chases after us through the corridors of history, committed to preserving our greatest joys.

The Bible is ultimately the story of God’s love for us.

In preparing for our study in Zechariah 3:1-7, let’s begin with the most critical issue: How to read the Bible. This may surprise you, but how we read the Bible changes everything about how we understand and experience the Christian life. If we get this wrong, we will undoubtedly wander down a path of misdirection.

As moderns, we have learned a way of reading that feels “normal” because it’s all we know. While it works in the classroom and the boardroom, it works against us when it comes to Scripture.

Let’s dig in and explore how God can meet us through the Bible.

The Genius of the Bible

Any author or speechwriter will affirm that effective communication begins with understanding the audience. This determines what information to include, how to arrange it, and what supporting details are necessary to convey this message to this audience.

What if the audience is people of all generations, races, ethnicities, and cultures? How do you create a message that will endure for millennia, communicate to all civilizations, languages, and customs, and be accessible to all people?

That is the ultimate communication challenge!

So how does God tell the story of Creation, His love, and desires to communicate the fullness of these foundational truths to a constantly changing historical and cultural audience?

That’s what the Bible intends to do.

For example, in the rough-and-tumble neighborhood of the Ancient Near East, how do you convince an unaware people that you created them with a purpose, that you are a personal and relational God, and that you love them deeply?

The historical context required a hands-on, scratch-and-sniff approach—a curriculum of interactive object lessons. There was something for every learning style: ceremonies, rituals, written instructions, songs, and plenty of things to feel, smell, hear, and taste.

God used the design, colors, and materials of a building and its furniture to point to the awe-inspiring nature of His love, along with animal blood, scents, and smoke, to communicate profound truths about our need for such love.

While the Bible is immediately relevant to our modern high-tech lives, making sense of its unfamiliar history, geography, culture, customs, and characters requires us to apply ourselves.

Humility serves us well as 21st-century Bible readers. We can’t impose our cultural frame of reference on ancient societies, practices, beliefs, and people.

(We’ll introduce a simple tool in just a moment.)

Reading the Bible, if we do not do it rightly, can get us into a lot of trouble . . .

It is not sufficient to place a Bible in a person’s hands with the command, “Read it.” This is quite as foolish as putting a set of car keys in an adolescent’s hands, giving him a Honda, and saying, “Drive it.” And just as dangerous. The danger is that in having our hands on a piece of technology, we will use it ignorantly, endangering our lives and the lives of those around us; or that, intoxicated with the power that the technology gives us, we will use it ruthlessly and violently.

For print is technology. We pick up a Bible and find that we have God’s word in our hands, our hands. We can now handle it. It is easy enough to suppose that we are in control of it, that we can use it, and that we are in charge of applying it wherever, whenever, and to whomever we wish without regard to appropriateness or conditions.

—Eugene Peterson, Eat This Book, 81-82.

Interacting with the Bible

This is a big deal.

Our literate culture equips us to read and gives us access to a printed (or digitized) Bible, leaving us to assume that we know how to interact with it.

As we approach Scripture, our lifelong, educationally enhanced training kicks in, immediately putting us in control of the process. We sift through large quantities of data, analyze it for helpful information, and synthesize it into principles—“takeaways”—that we use for problem-solving and meeting our needs.

As we read the Bible through the filter of our own perceptions, our own desires, our own wants, and our own needs, we search for information, techniques, methods, and systems to enhance our ability to create a life that functions according to our desires.

We control the process.

We master the text.

While our modern approach to reading the Bible is unconscious and all we know, it is a critical departure from how the Bible instructs its non-literate audience to interact with Scripture.

Letting the Bible Read Us

While reading the Bible for information is necessary, it is not sufficient for spiritual growth.[1] By itself, it can even work against the formation of the Christian soul.[2]

While it’s essential to master the text, more importantly, the text is intended to master us— to form the way we live our lives, not merely make an impression upon our minds or feelings.

. . . The informational mode is only the “front porch” of the role of Scripture in spiritual formation. It is the point of entry into the text. But once we have crossed the porch, we must enter into that deeper encounter with the Word that is the formational approach, if we are to experience our false self being shaped by the Word toward wholeness in the image of Christ.[3]

Alive to God in Scripture

During Biblical times, literacy rates were extremely low, and few had access to hand-copied scrolls. Until the mid-15th century and the invention of the printing press, exposure to Scripture was primarily through the spoken word. Ingenious, subtle literary patterns within the text made it easier to recall so one could remember and meditate upon it.

The Old Testament Hebrew word, hagah, describes this internal process of “chewing on” Scripture where God encounters us.

This book of the law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall hagah on it day and night, so that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it; for then you will make your way prosperous, and then you will have success.[4]

Hagah is a word that phonetically imitates the sound of its source of meaning[5] — like a hungry lion fiercely and intently murmuring over its food. It includes thinking, studying, reflecting, imagining, chewing on, considering, ruminating, pondering, musing, devising.[6] And from its earthy background, it evolved to mean “the thinking of the heart,”[7] and later:

To work out the personal meaning by careful thought. [8]

This “gnawing” on Scripture is how we make room for God to encounter us in our minds, emotions, conscience, and will. Here, we are accompanied, reminded, affirmed, challenged, and invited to embrace what we can’t see or might never consider on our own.

With respect to biblical reading, we willingly stand ourselves before the text and await its address, ready for the Word to exercise control over (us). It requires waiting before the text. You must take time with it to hear what it says.[9]

In allowing the Scriptures to master us, we discover God’s possibilities for our lives.

Understanding the Bible: The Ladder of Abstraction

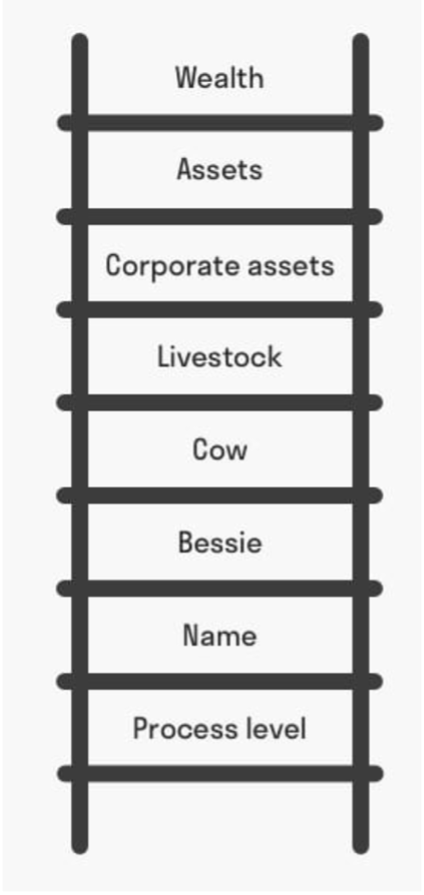

The ladder of abstraction[10] is a simple tool that helps us bring concepts communicated to an ancient culture into our 21st-century world. It’s like a bridge connecting two time-bound cultures, moving from concrete objects or practices in the ancient text to the values and principles they communicate.

Bessie the Cow and the Ladder of Abstraction

Let’s think about how we can understand a cow named Bessie. These descriptions range from abstract (top of the ladder) to concrete (bottom):

- wealth (most abstract, top of the ladder)

- assets

- farm assets

- livestock

- cows

- the cow named Bessie

- atoms and molecules forming Bessie (most concrete, bottom of the ladder)

Any of these concepts can be appropriate depending on the context. Farm children most likely think highly concretely, referring to the cow with the bell on her neck as “Bessie.”

At feeding time, the farmer probably thinks about cows and livestock. Then, when selling the farm, Bessie and the other cows are considered farm assets, ultimately equating to wealth.

The higher up the ladder, the more abstract the idea, language, or thought. The lower you are on the ladder, the more concrete the idea, language, or thought.

How Biblical principles come alive in our modern world

Some Old Testament teachings directly translate into our modern culture.

For example, the Ten Commandments. Principles like “You shall not murder,” “You shall not steal,” “You shall not commit adultery,” “Honor your father and mother,” and “Keep the Sabbath day holy” are not culture-bound and can be brought straight across into our lives.

However, other teachings are particular to ancient Israelite culture and religion and don’t make sense in our culture if we try to apply their concrete meaning literally.

For example, “Don’t wear clothes made of both wool and linen,” “Never boil a baby goat in its mother’s milk,” and “Don’t get tattoos.”

These principles are culture-bound and don’t make sense to us in concrete terms. Our work is to climb the ladder of abstraction and find the principle or value of what is being communicated so that we can incorporate it into our world. (See examples below)

REFLECTION QUESTIONS

In what significant ways might your life be different if you could encounter and be encountered by God in Scripture?

What would need to change for this to become real for you?

3-2-1

Three key insights from this study

Two questions you come away with

One personal prayer related to this material

[2]. The School of Obedience, Andrew Murray (St. Paul, MN: Wilder Publications, 2006) 54. “Unless we be aware, the Word, which is meant to point us away to God, may actually intervene and hide Him from us. The mind may be occupied and interested and delighted at what it finds, and yet, because this is more head knowledge than anything else, it may bring little good to us. If it does not lead us to wait on God, to glorify Him, to receive His grace and power for sweetening and sanctifying our lives, it becomes a hindrance instead of a help.”

[3]. Shaped by the Word, M. Robert Mulholland (Nashville, TN: Upper Room Books, 2001) 59.

[4]. Joshua 1:8. See also, Psalm 1:1-2 and Psalm 119:12-16

[5]. Known as an onomatopoeia.

[6]. So, Psalm 2:1; Proverbs 24:2

[7]. In the Jewish Qumran community around the time of Jesus, hagah meant, “in the thought of my heart.”

[8]. Hagah is often translated as, meditate, a confusing term in our culture with a wide range of meanings. The goal of Eastern meditation is to empty the mind and become detached from feeling and thought. Its objective is to realize there is no individual self and that the real self is part of the divine godhead, the ultimate reality. In contrast, hagah means to fill the mind with the Scriptures, reflecting upon their meaning for our lives, paying attention to God’s personal, living Presence made real through His invitations, corrections, affirmations, and direction. The goal is to live according to our true identity, as God’s beloved, actively partnering with the process of being conformed to the image of Jesus for the sake of others.

[9]. Shaped by the Word, M. Robert Mulholland (Nashville, TN: Upper Room Books, 2001) 59.

[10]. S. I. Hayakawa, Language in Action (New York City, New York, Harcourt and Brace, 1941).